Tea 101: The Six Categories and the Role of Oxidation

If you caught our last tea journal, you’ll remember that all true tea comes from the same magical plant: Camellia sinensis. But then… what makes green tea green and black tea black? The secret isn’t where it grows. It’s what happens after the leaves are plucked. That secret is oxidation.

Oxidation is the natural process that transforms a tea leaf’s flavor, color, and character. Think of it like the difference between raw and roasted nuts, or fresh versus sun-dried tomatoes. It’s transformation through time, air, and intention.

In tea, this transformation is driven by the oxidation of polyphenols, the compounds responsible for much of tea’s flavor and benefits. This can happen in two ways: one through natural enzymes (biochemical), and the other through exposure to heat, air, or time (chemical). How much these polyphenols are allowed to oxidize determines what type of tea you end up with.

Still sounding a bit science-y? Let’s make it easier. Think of it like coffee roasting: light, medium, dark. Just like a lightly roasted coffee keeps more of its original character and caffeine, a lightly oxidized tea, like green or white tea, holds onto more of its original polyphenols and fresh, grassy notes.

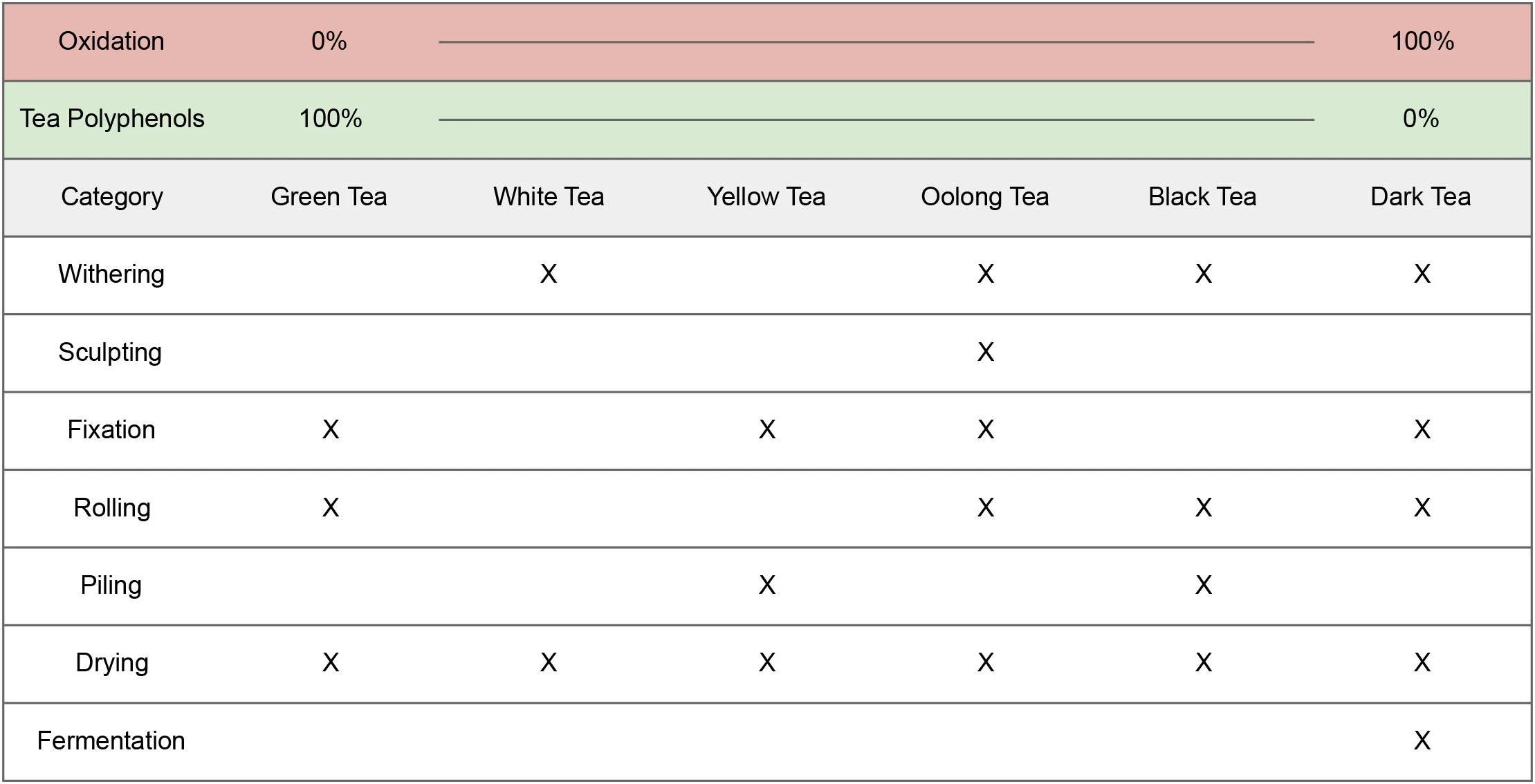

That’s why most teas fall into one of six basic categories: Green, White, Yellow, Oolong, Black, and Dark. Each one is defined by its level of oxidation, from almost none to fully oxidized.

Green Tea

Green tea might just be the most beloved and certainly one of the most iconic types of tea, both in its birthplace, China, and around the world. Traditionally, it’s described by the “three greens”: the fresh green of the dry leaf, the soft green of the steeped brew, and the gentle green of the leaf after infusion. But truthfully, green tea comes in many shades, and color alone doesn’t tell the whole story.

So what really makes a tea green? It all comes down to how it’s crafted. Right after harvest, the fresh tea leaves go through a crucial step called fixation, where they’re briefly exposed to high heat to stop oxidation in its tracks. This quick heating deactivates the natural enzymes in the leaf that would otherwise trigger oxidation. It preserves that vibrant green color and all the good stuff inside.

Then comes rolling, where the leaf is gently pressed and shaped. This breaks down the inner cell walls just enough to let flavor-carrying juices rise to the surface. After that, it’s time to dry, usually with some level of heat. This step locks in the aroma, defines the flavor, and ensures just the right texture and moisture level.

Because green tea skips the oxidation process entirely, it holds on to almost 100 percent of its original tea polyphenols. That’s a big reason why it’s so celebrated for its wellness benefits. It’s rich in antioxidants and catechins, compounds studied for heart health, blood sugar balance, liver function, and cognitive support. Research has found it can help reduce cholesterol, aid metabolic function, and even assist in regulating blood glucose over time.

White Tea

White tea is one of those rare gems. People either fall completely in love with it or find themselves wondering what the fuss is all about. There’s hardly any middle ground, especially when it comes to those ethereal versions made from tender tea buds. The reason? Its flavor is famously delicate, almost whisper-soft, and it takes a refined, curious palate to catch all its subtle notes.

What sets white tea apart is just how natural it is. Among all tea types, it goes through the fewest processing steps: just withering and drying. Most of the time, the withering happens under the sun. Picture this: on a cool, sunny day, fresh tea buds are gently laid out on woven screens, basking in direct sunlight. After a while, they’re brought into the shade to rest, then returned to the sun in cycles. It’s slow, gentle, and beautifully simple.

Unlike green tea, which undergoes heat to halt oxidation, white tea walks a fine line. Its enzymes are never fully shut down or sped up. This allows for a slow, quiet transformation where both enzymatic and non-enzymatic oxidation gradually unfold. As a result, nearly 90 percent of the tea polyphenols are preserved right after it’s made.

But here’s where white tea gets even more magical. With time, it continues to evolve. As the months and years pass, the remaining polyphenols keep transforming, mellowing the tea into something smoother, softer, and naturally sweeter. It’s why aged white tea has such a devoted following: time, quite literally, becomes part of the craft.

Yellow Tea

Not many people have heard of yellow tea, and if you haven’t either, you’re not alone. Even in China, where tea is a part of daily life, yellow tea remains a bit of a mystery to most.

At first glance, it looks and sounds a lot like green tea. Both start with a step called fixation, where the leaves are exposed to heat to stop enzymatic oxidation, and both end with a careful drying process. But yellow tea includes one quiet, magical step that sets it apart: steamed piling.

This extra step is done after the oxidation enzymes have already been halted. It doesn’t restart oxidation in the typical enzymatic sense. Instead, it gently encourages non-enzymatic oxidation, allowing the tea’s character to deepen and mellow. By the end of this slow transformation, yellow tea retains around 70 to 90 percent of its original tea polyphenols, striking a beautiful balance between freshness and complexity.

Oolong Tea

Of all the tea categories, oolong has the most intricate production process. It requires not only a series of detailed steps but also a great deal of time. In fact, crafting a high-quality oolong can take more than half a year to complete.

At the heart of oolong’s craftsmanship are techniques such as withering, fixation, rolling, and drying. What sets it apart is one unique step found only in this category: sculpting.

So what exactly happens during sculpting? It is a rhythmic cycle of gently shaking the tea leaves, then letting them rest, repeated again and again. This intentional bruising causes the edges of the leaves to collide, which initiates enzymatic oxidation. During the resting periods, oxidation slows slightly, while moisture from the stems gradually moves outward, preparing the leaves for the next round. It is a delicate process that demands exceptional skill and patience.

Depending on how extensively the sculpting is carried out, the remaining tea polyphenol content in the finished oolong can vary significantly, ranging from about 30 percent to 70 percent. This broad spectrum is what gives oolong its remarkable versatility and makes it a beautiful bridge between green and black teas.

There’s a well-loved Chinese saying that describes the ideal oolong leaf: “Three parts red, seven parts green.” It refers to the perfect balance of oxidation, where the edges of the leaf gently blush while the center remains fresh and vibrant.

Black Tea

Black tea is perhaps just as beloved as green tea, if not more so, thanks in large part to its bold and full-bodied character. To develop that signature profile, black tea goes through four essential steps: withering, rolling, piling, and drying.

Here is where it gets interesting. Unlike green or oolong tea, where rolling happens after enzymatic activity has been halted, black tea is rolled while the oxidation enzymes are still active. In other words, the leaves are still very much “alive” during this stage. As they are shaped and twisted, enzymatic activity intensifies and the cell walls break down, setting the stage for the next step: piling.

Piling is where the magic of oxidation truly unfolds. While yellow tea experiences non-enzymatic oxidation after fixation, black tea undergoes enzymatic oxidation during piling. This phase transforms the tea’s chemical makeup, deepening its color, aroma, and flavor. By the end of piling, only about 10 to 20 percent of the original tea polyphenols remain.

Finally, the drying step seals it all in. High heat is applied to stop any remaining enzymatic activity and to lock in the tea’s defining characteristics.

But black tea’s transformation isn’t just chemical, it’s also historical. Originally cultivated in China for both domestic use and export, black tea captured British tastes in the 18th and 19th centuries. It became more than a drink; it became a ritual of refinement and status. In a bid to break China’s monopoly, the British East India Company sent botanist Robert Fortune to secretly obtain tea plants and tea-making knowledge from China and bring them to British-controlled India. This act of botanical espionage marked the beginning of India’s own tea empire and forever changed the global tea landscape.

Dark Tea

Dark tea is one of those hidden gems in the tea world. It is well known in China, but still flies under the radar in many other places. What sets it apart is not just its earthy richness or the deep calm it brings, but the unique two-phase process that gives it life.

Phase One: From Leaf to “Rough Tea”

It all starts with steps that might sound familiar: a bit of extra withering, followed by fixation, rolling, and drying, much like green tea. During this time, oxidation occurs naturally. But here’s the twist: at this stage, the tea is not considered finished. It is known as “rough tea,” and it patiently waits for the next chapter of its transformation.Phase Two: The Magic of Fermentation

Now comes the step that makes dark tea truly special: fermentation. Once the rough tea is sorted and prepared, it is gently piled in a space with carefully managed humidity and temperature. The tea is left to rest, then turned regularly. This warm, humid environment becomes a haven for microbes, which release enzymes that begin the slow fermentation process. This phase can take weeks or even months.

Once the fermentation has run its course, the softened leaves are steamed and either packed loose or pressed into beautiful bricks or cakes. From there, the tea moves into the cellar to rest and age, often for years. During this slow maturation, its flavor deepens and evolves. By the end of this journey, nearly all of the original tea polyphenols have transformed, leaving behind something entirely new: smooth, mellow, and wonderfully complex.